http://www.eastasiaforum.org/2018/04/19/what-is-socialist-about-socialist-east-asia/

What is socialist about socialist East Asia?

Author: John Gillespie, Monash University

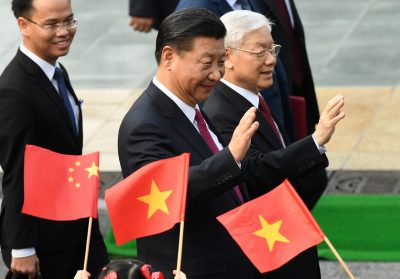

On the 100th anniversary of the Russian October Revolution, the general secretaries of Asia’s ruling communist parties, Xi Jinping in China and Nguyen Phu Trong in Vietnam, reaffirmed their commitment to the socialist project. Over 70 years ago communist parties in Asia turned to the Soviet Union for inspiration. On gaining power, they enacted constitutions and established institutions that, with varying degrees of faithfulness, replicated Soviet regulatory models.

The collapse of the Soviet Bloc was accompanied by the literal collapse of structures and organisations previously considered indestructible, such as the Berlin Wall and statues venerating socialist heroes. Much subsequent analysis about socialist Asia promptly assumed the end of socialism and a transition to some kind of liberal governance. But the institutions of socialism — especially the mechanisms of economic regulation — have proven resilient and adaptable.

If the core characteristic of a socialist society is a commitment to an egalitarian society, then China’s and Vietnam’s records are mixed. Market reforms that dismantled the command economy have raised millions out of poverty, but also produced inequalities in wealth not seen for generations.

Although the socialist commitment to egalitarianism has faded, party leaders still actively use regulatory techniques that were borrowed from the Soviet Union to manage the command economy. These techniques include politically embedded regulation, data collection and monitoring, and mass-mobilisation campaigns. They are used to order a mixed-market economy that combines relatively high levels of state participation with capitalist economic institutions, such as markets, corporations and other forms of investment vehicles.

State ownership of the means of production formed the core regulatory objective of the command economy. Some commentators estimate that — far from withering away under mixed market reforms — state-owned enterprises (SOEs) currently generate a third of GDP in China and Vietnam. National champions are encouraged to list on stock markets and take on global markets.

Despite decades of corporate law reforms, and privatisation, the Chinese state has maintained its control over SOEs. The use of informal channels of control reflects the personalised regulatory administration that developed during the command economy. Personal lines of control between the state regulators and SOEs conflated Soviet command regulation with Confucian moral rule. In the mixed-market economy, this regulatory practice has evolved into a type of politically embedded economic management. Regulators use a combination of internal party and state channels, as well as statutory instruments, to transmit instructions to SOEs and party units embedded in large private firms.

As a consequence, SOEs pursue objectives that extend well beyond the interests of shareholders and employees, such as directing and coordinating the ‘commanding heights’ — those elements of industry most essential to the economy — together with many other key economic sectors. As in the command economy, SOEs are treated as integral components of Party-state governance, and not just the objects of state regulation.

In another continuity with the command economy, the state uses data collection and monitoring to regulate the economy. Although this type of regulation through auditing has become important in neoliberal economies, its use in socialist Asia owes much to Russian communist revolutionary Lenin’s faith in modern scientific management. Efforts by central planners in the command economy to gain accurate information from SOEs often resulted in fabricated data and tactical manoeuvring by firms to place assets beyond central scrutiny — creating a regulatory environment of mistrust. In response the state devised additional layers of monitoring and accountability that only deepened the mistrust.

Current economic regulation reflects this culture of mistrust. Auditing continues to stress upward accountability, so that SOEs and large companies are encouraged to focus on centralised directives. Regulation through data collection and monitoring has not made directors more personally accountable because SOEs do not function in environments in which directors are disciplined by market incentives.

Governments in socialist Asia have also enthusiastically embraced the use of key performance indicators to rank and standardise market and social behaviour. For example, the Chinese government is developing ‘social credit’ indicators that integrate citizens’ consumer behaviour, conduct on social networks and legal violations into a single, algorithmically determined ‘sincerity’ score that creates a numeric index of trustworthiness.

In another show of recycling from the command economy, the party continues to use mass-mobilisation and emulation campaigns to communicate with the ‘masses’ and model correct behaviour. The emergence of the mixed-market economy did not signal a retreat from this mode of regulation but rather a reconfiguration of how the party sought to persuade and educate the masses. Although party leaders exalt the masses as the cultural base of society, they also worry about the ‘quality’ of the population, believing that low levels of education and ‘civilisation’ might impede industrialisation and modernisation.

Campaigns aim to raise the ‘quality’ of citizens by inculcating values associated with a ‘socialist society with spiritual civilisation’ in China and an ‘equitable and civilised society, steadfastly advancing towards socialism’ in Vietnam. Interestingly, party leaders continue to assert the right to engineer the national character long after they abandoned cradle-to-grave social welfare and other trappings of socialist paternalism.

There are continuities, recurrences and cross-fertilisations between the regulatory technologies of the command economy and capitalist institutions, such as markets and corporations. One consequence of this variegated regulation is that China and Vietnam are simultaneously transitioning out of socialism and transforming socialism. Regulatory technologies from the command economy are resilient, not only because they are promoted by the Party-state, but also because many people within and outside the state find them familiar and credible.

John Gillespie is a professor in the Department of Business Law and Taxation at Monash University.