핵심: 반도체는 IBM과 인텔의 기술이다. 반도체 제조 노동자의 산업재해(유산, 기형아 출산, 암 발병, 생리 불순)가 잇따르고 여론이 악화되었다. 미국 내 반도체 생산이 중단되었고, 반도체 생산라인은 임금이 싸고 노동자의 눈치를 보지 않아도 되는 곳, 바로 한국으로 옮아갔다. IBM은 이 같은 계약 사실에 대해 입을 굳게 다물었지만 한국의 두 회사는 자국 언론에 자랑하기 바빴다. 작업장에서 독성물질을 몰아내겠다는 미국 반도체 업계의 다짐까지는 바다를 건너지 못했다. 미국의 여성 노동자를 대신해 한국의 수많은 여성과 미래에 태어날 아이들이 그 대가를 치렀다.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2017-06-15/american-chipmakers-had-a-toxic-problem-so-they-outsourced-it

American Chipmakers Had a Toxic Problem. Then They Outsourced It

Results in epidemiology often are equivocal, and money can cloud science (see: tobacco companies vs. cancer researchers). Clear-cut cases are rare. Yet just such a case showed up one day in 1984 in the office of Harris Pastides, a recently appointed associate professor of epidemiology at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

A graduate student named James Stewart, who was working his way through school as a health and safety officer at Digital Equipment Corp., told Pastides there had been a number of miscarriages at the company’s semiconductor plant in nearby Hudson, Mass. Women, especially of childbearing age, filled an estimated 68 percent of the U.S. tech industry’s production jobs, and Stewart knew something few outsiders did: Making computer chips involved hundreds of chemicals. The women on the production line worked in so-called cleanrooms and wore protective suits, but that was for the chips’ protection, not theirs. The women were exposed to, and in some cases directly touched, chemicals that included reproductive toxins, mutagens, and carcinogens. Reproductive dangers are among the most serious concerns in occupational health, because workers’ unborn children can suffer birth defects or childhood diseases, and also because reproductive issues can be sentinels for disorders, especially cancer, that don’t show up in the workers themselves until long after exposure.

Digital Equipment agreed to pay for a study, and Pastides, an expert in disease clusters, designed and conducted it. Data collection was finished in late 1986, and the results were shocking: Women at the plant had miscarriages at twice the expected rate. In November, the company disclosed the findings to employees and the Semiconductor Industry Association, a trade group, and then went public. Pastides and his colleagues were heralded as heroes by some and vilified by others, especially in the industry.

SIA, representing International Business Machines Corp., Intel Corp., and about a dozen other top technology companies, established a task force, and its experts flew to Windsor Locks, Conn., to meet Pastides at a hotel near Bradley International Airport. It was Super Bowl Sunday, January 1987. “That was a day I remember being at a tribunal,” Pastides says. The atmosphere “bordered on hostility. I remember being shellshocked.” Soon after the meeting the panel formally concluded that the study contained “significant deficiencies,” according to internal SIA records. Nevertheless, facing public pressure, SIA’s member companies agreed to fund more research.

Scientists from the University of California at Davis designed one of the biggest worker-health studies in history, involving 14 SIA companies, 42 plants, and 50,000 employees. IBM opted out, hiring Johns Hopkins University to study its plants, because IBM executives said their facilities were safer than the others, recalls Adolfo Correa, one of the lead Johns Hopkins scientists.

In epidemiology, follow-up studies usually get bigger and tougher, and for that reason they often contradict one another. But by December 1992, something rare had happened. All three studies—all paid for by the industry—showed similar results: roughly a doubling of the rate of miscarriages for thousands of potentially exposed women. This time the industry reacted quickly. SIA pointed to a family of toxic chemicals widely used in chipmaking as the likely cause and declared that its companies would accelerate efforts to phase them out. IBM went further: It pledged to rid its global chip production of them by 1995.

Pastides felt vindicated. More than that, he considered the entire episode one of the greatest successes in public-health history, as do others. Despite industry skepticism, three scientific studies led to changes that helped generations of women. “That’s almost a fairy tale in public health,” Pastides says.

Two decades later, the ending to the story looks like a different kind of tale. As semiconductor production shifted to less expensive countries, the industry’s promised fixes do not appear to have made the same journey, at least not in full. Confidential data reviewed by Bloomberg Businessweekshow that thousands of women and their unborn children continued to face potential exposure to the same toxins until at least 2015. Some are probably still being exposed today. Separate evidence shows the same reproductive-health effects also persisted across the decades.

The risks are exacerbated by secrecy—the industry may be using toxins that still haven’t been disclosed. This is the price paid by generations of women making the devices at the heart of the global economy.

In 2010 a South Korean physician named Kim Myoung-hee left her assistant professorship at a medical school to head a small research institute in Seoul. For Kim, who’s also an epidemiologist, it was a chance to spend more time on the public-health research she’d embraced as a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard five years earlier.

In her new post, a series of cancer cases in South Korea’s microelectronics industry drew her interest, including one particular episode that had caught the public eye: Two young women working side-by-side at the same Samsung Electronics workstation and using the same chemicals contracted the same aggressive form of leukemia. The disease kills only 3 out of every 100,000 South Koreans each year, but these young co-workers died within eight months of each other. And their disease was among those most clearly tied to carcinogens. Activists discovered more cases at Samsung and other microelectronics companies, mostly among young women. Industry executives denied any link.

Kim began compiling and analyzing occupational-health studies about semiconductor workers worldwide, a body of work that had drawn little attention in South Korea despite the industry’s importance there. She found 40 different works published by 2010, and virtually every one mentioned exposure to toxic chemicals. “I had no idea that this is a chemical industry, not the electronics industry,” she says.

Physics drives the design of microchips, but their production is mostly about chemistry. In a basic sense, chemicals and light combine to photographically print circuits onto silicon wafers. Gordon Moore, a founder of Intel and a major figure in the creation of the modern chip in 1960, is a chemist. He worked closely on the printing process with a physicist named Jay Last. “We were putting into industrial production a lot of really nasty chemicals,” Last said in an interview he did with Moore for an oral history project of the Chemical Heritage Foundation. “There was just no knowledge of these things, and we were pouring stuff down into the city sewer system.”

Moore recalled how, years later, when workers dug up the pipes beneath Intel, they discovered the “bottom was completely eaten out the whole way along, and that was just about the time we really started recognizing how much you had to take care of this.” Authorities would end up designating more Superfund hazardous waste sites in Santa Clara County, the heart of Silicon Valley, than in any other county in the U.S.

As Kim learned in her scientific review, one critical chemical cocktail in the printing process is called a photoresist. It’s a light-sensitive compound that allows circuit patterns to be photographically printed on the chips. Moore and Last suggested in their oral-history interview that the dangers of the chemicals they were using were unknown in 1960, but studies linking photoresist ingredients to dangers dated to the 1930s. The toxic ingredients were called ethylene glycol ethers, or EGEs. They also became key ingredients in solvent mixtures known as strippers, which are used to clean the chips during printing.

Kim could see that Pastides pointed to these same chemicals when he did his study at Digital Equipment, as did the Johns Hopkins scientists working with IBM. The IBM study found miscarriage rates tripled for women who worked specifically with EGEs. Separate studies showed EGEs easily permeated rubber gloves, like water through a net, and that skin absorption was the most dangerous route, leading to exposure rates 500 to 800 times above the level deemed safe. The dangers were so abundantly clear that the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration in 1993 formally proposed exposure levels so minute that, practically speaking, companies would have to ban EGEs to comply.

Kim’s study took her through not only all of that research but also the studies done since. Historical reproductive-health studies connected microelectronics production to fatal birth defects in the children of male workers, childhood cancers among the children of female workers, and infertility and prolonged menstrual cycles.

Yet in virtually every study published since the 1990s, Kim read one form or other of the same phrase: The global semiconductor industry had phased out EGEs in the mid-1990s, signaling the end of reproductive-health concerns. The statements made sense. Not only had IBM and other companies publicly announced that the use of EGEs had been discontinued, but the chemicals also had become classified as Category 1 reproductive toxins under international standards, and European regulators had placed them on a list of the most highly toxic chemicals known to science, designating them Substances of Very High Concern.

Still, something nagged at Kim. In focus groups, young South Korean women working in chip plants told Kim’s colleagues it was not uncommon to go months, or even a year, without menstruating. (Some saw these potentially ominous changes to their reproductive systems as blessings, not warnings. It was just easier not to have periods.) As in the U.S., women dominated production jobs in South Korea’s microelectronics industry, which employs more than 120,000 of them, mostly of childbearing age; they’re often recruited right out of high school. Kim and a colleague decided they needed to conduct a new reproductive-health study. They faced a challenge, however, that Pastides and the other U.S. researchers hadn’t, at least on the front end: a lack of industry cooperation.

In 2013 they persuaded a member of South Korea’s parliament to pry loose national health-insurance data. They got five years of physician-reimbursement records through 2012 for women of childbearing age working at plants owned by the country’s three largest microelectronics companies: Samsung, SK Hynix, and LG. Samsung and SK Hynix accounted for the vast majority of women in the study, as the two have long been among the world’s largest chipmakers. The data covered an average of 38,000 women per year. From that number, the researchers looked at the records of those who had gone to doctors for miscarriages.

The results were both undeniable and shocking to Kim, just as they had been for Pastides almost three decades earlier. She found significantly elevated miscarriage rates and a rate for those in their 30s almost as high as in the U.S. factories. And the findings were conservative, because many women don’t go to the doctor for miscarriages, and because production workers couldn’t be separated in the study from those who worked in offices. “This was not the result I had expected,” Kim says.

In a paper they published on their study, Kim and her colleagues repeated the mantra of the earlier research: EGEs had been phased out of the industry. In their conclusion, though, they added a hedge, saying they couldn’t be certain. They also noted an array of other reproductive toxins and environmental hazards in the plants, including ionizing radiation. And they ended with this cautionary note: “Given that our data came from the three biggest companies in Korea, it is plausible to assume that workers in small-sized companies of Korea, or working in developing countries, are more exposed to such risk.”

After the outcry in the U.S. in the 1990s, chemical companies said they’d changed the formulations for the photoresists and other products they supplied to chipmakers, including those in Asia. But testing data obtained by Bloomberg Businessweek show that changes weren’t made quickly or, in some cases, completely.

In 2009, South Korean scientists tested a total of 10 random samples taken from drums of photoresists at a Samsung plant and an SK Hynix plant. Because concern then focused on leukemia, the photoresists were tested only for toxins related to that disease. One was benzene, which was known to cause the rare form of leukemia that killed the Samsung co-workers, and another was the most toxic of the EGEs, a chemical commonly called 2-Methoxyethanol, or 2-ME. Tests showed 2-ME in 6 of the 10 photoresist samples, according to a copy of the results. Of the two samples that contained the highest concentrations, one came from SK Hynix, the other from Samsung.

The South Korean scientists didn’t record the names of the chemical companies that made and sold the barrels tested, but they did record product numbers, and those, when matched against patent data, show that the two photoresists with the highest concentrations of 2-ME were made by the same manufacturer: the Shin-Etsu Chemical Co. in Tokyo.

In its annual report for that fiscal year, Shin-Etsu said it was “the leading photoresist manufacturer in the world, with a share of around one-third of the market.” That raises the specter of exposure to 2-ME at semiconductor plants across Asia. A company in Taipei called Topco Scientific Co. is the exclusive distributor for Shin-Etsu chemicals in Taiwan and China, and photoresists are its top source of revenue, according to securities filings. A Topco executive who oversees photoresist sales confirmed that the two specific products with the highest concentrations of 2-ME have been sold to semiconductor companies in Taiwan and China for years.

A spokesman for Shin-Etsu, Tetsuya Koishikawa, initially declined to discuss the chemical components of its products or issues related to reproductive health in the plants of its customers. In a follow-up email statement, he said that Shin-Etsu has never used 2-ME in its photoresists.

In 2015, South Korean scientists followed up on, and expanded, the previous round of photoresist tests, drawing random samples from seven semiconductor makers. This time, samples from Samsung and SK Hynix came up negative for 2-ME, but the sample taken from a smaller company tested positive. (The testing data were shared with Bloomberg Businessweekon the condition that the company not be identified.)

SK Hynix declined to comment. Samsung says it can be certain only that EGEs were completely removed from its production by 2011, because that’s the extent of its internal record keeping, but Ben Suh, a spokesman for Samsung, says the company believes a transition away from EGEs began earlier, as its suppliers started changing the chemical mixtures after the mid-1990s. He says that while Samsung was aware of the 2009 test results showing 2-ME at its plant, it was unable to internally confirm or replicate them.

The company also says, “Samsung Electronics has a strict workplace policy for pregnancy and maternity rights, and programs are in place to provide special care for expecting mothers. Pregnant women are not allowed to handle chemical substances, take night shifts, or work extra hours.”

It’s troubling that 2-MEs turned up at a smaller chipmaker in 2015. In recent years many of the biggest semiconductor makers have automated significant steps in their chipmaking to boost production and revenue. This has reduced, though not eliminated, the physical handling of chemicals in those plants and so it’s reduced the potential for exposure. But production at companies with older, nonautomated plants hasn’t diminished. Thousands of women at these plants across Asia may still be exposed to EGEs.

That the risks could persist overseas was flagged more than two decades ago by the Johns Hopkins researchers working at IBM. They knew that EGEs were cheap, effective, and abundantly available and that less-dangerous alternatives were far more expensive. Their published report cited the higher costs of safety and specifically warned that could mean the dangers would persist overseas.

According to Correa, the lead epidemiologist on the IBM study, company executives received a copy of the paper carrying that warning in 1995. That’s the year by which IBM had committed to discontinuing the use of EGEs at its plants. It’s also the year IBM executives negotiated massive, multiyear production contracts to have two other companies supply it with memory chips—Samsung and SK Hynix.

Although IBM was silent about these deals at the time, Samsung and SK Hynix executives disclosed them in Korean-language publications. IBM was the biggest among several U.S. companies with which the two South Korean chipmakers were then signing supply deals totaling about $165 billion. “Because of the secrecy clauses of the contract, the exact size of the deal and the names of companies cannot be disclosed,” Kim Young-hwan, then in charge of SK Hynix sales to the U.S., told the newspaper Kyunghyang Shinmun in its March 1, 1996, edition. Still, he said his company was about to “become IBM’s largest supplier of semiconductors by delivering 20 percent of their demand for the next five years.” Samsung’s contract with IBM was also for five years.

After IBM started buying memory chips from South Korea, it cut production in at least one of the plants where Correa and his colleagues found the elevated miscarriage rates. Other members of the Semiconductor Industry Association also made deals in South Korea similar to IBM’s, including Motorola, Texas Instruments, and HP. Intel began buying Samsung memory chips to put into its then world-dominating Pentium-processor chipsets in 1996. To the extent the South Koreans continued using products containing EGEs, the industry was in effect trading exposure in U.S. workers for exposure in women overseas.

Citing client confidentiality, Suh, the Samsung spokesman, declined to comment on whether IBM or any other U.S. company demanded health and safety protections for Korean women producing chips under contracts initiated after the U.S. miscarriage studies. IBM declined to comment for this article.

Samsung and SK Hynix have dominated global production of memory chips for two decades—they controlled more than 74 percent of the market in 2015. Their chips are in iPhones, Android phones, laptops, cars, televisions, and game consoles—anything with an electronic brain. It’s a safe bet that virtually every consumer in the industrialized world has purchased products containing memory chips made by Samsung or SK Hynix.

The health effects might have migrated and persisted overseas, but they’ve been quietly playing out across the U.S. in birth-defect lawsuits. Some of these suits are still pending. Starting with IBM in 1997, more than two dozen technology and chemical companies have been sued in at least 66 separate civil actions nationwide, according to court records compiled by Bloomberg Businessweek. Some are for cancer, but plaintiffs have included at least 136 children with birth defects or childhood diseases allegedly linked to maternal toxic exposures, records show.

The leading force behind the litigation is a New York class-action lawyer named Steven Phillips. None of his birth-defect cases has gone to trial, and many have been settled under secret terms, including those against IBM, according to court records and attorneys who have worked with Phillips. One birth-defect case was settled as recently as July 2015 against Arizona-based ON Semiconductor Corp., according to Delaware court records. The settlement is sealed. ON Semiconductor denied liability. Phillips didn’t respond to requests for comment for this story.

The website for Phillips’s Manhattan law firm boasts that he’s landed “nine-figure confidential settlements with Fortune 500 manufacturers and chemical suppliers on behalf of dozens of adults suffering from cancer, and children born [with] birth defects, as a result of workplace exposure to toxic chemicals.” Semiconductors aren’t mentioned.

Kim, the epidemiologist, says the secrecy of these settlements is a reason there was so little discussion for so long of the risks in chipmaking. “It was not published in academic papers,” she says. “Just some hidden settlements between the companies and some victims.”

Even today, the chipmakers themselves sometimes don’t know what they’re bringing into their facilities and exposing their workers to. That’s what SK Hynix discovered in 2015 after hiring a team of university scientists to assess the toxic risks in two of its plants.

Some of their results were made public in Korean, but many of the findings remain confidential. An extract of the research reviewed by Bloomberg Businessweek shows scientists found that the plants used about 430 different chemical products each. These included more than 130 deemed to be dangerous enough that employees exposed to them must undergo special health checks; those chemicals are called CMR agents—shorthand for carcinogens, mutagens, and reproductive toxins. In addition to benzene and EGEs, they’ve historically included arsenic, hydrofluoric acid, and trichloroethylene.

The companies that make and sell these chemicals don’t disclose their proprietary formulations to chipmakers. For each of the 157 distinctive chemical ingredients scientists identified in the study commissioned by SK Hynix, there were more than two chemicals—a total of 363—that weren’t disclosed because of “trade secret” designations, according to researchers. Even the chip plants’ own health and safety managers have no idea what’s in many of the mixes, especially in the photoresists. That makes it difficult, if not impossible, to monitor what a given worker is being exposed to and to what degree. And the ingredients are constantly changing, as chipmaking technology advances.

Because of the reproductive toxins and carcinogens found in photoresists, semiconductor makers need to do their own regular, random tests to guard against exposure, the scientists say. They also concluded that there was an urgent need to establish a top-to-bottom total chemical surveillance system, which SK Hynix has said it’s putting in place. A change in South Korea’s trade-secrets law, adopted in 2015, will compel the release of more information, but it’s yet to be fully implemented.

The business of selling chemicals to chipmakers is worth $20 billion a year, according to a February 2016 report by Frost & Sullivan, a market research company in Mountain View, Calif. Pure EGEs are manufactured by at least 24 companies in 10 countries, according to a 2010-11 directory of chemical manufacturers published by SRI Consulting. U.S. producers include Dow Chemical Co., which makes EGEs in Texas, and Monument Chemical, which makes them in Kentucky. International producers include BASF in Germany, Switzerland-based Clariant, and Sinopec Tianjin, which is a subsidiary of the China Petroleum & Chemical Corp., the state-owned giant.

That’s just the mainstream. Go to Alibaba, and you’ll find five Chinese companies that specifically market EGEs for use in the electronics industry. “Electronic Grade 2-Ethoxyethanol with great price,” says one ad. Another declares: “High Quality … best price from China, Factory Hot Sale Fast Delivery!!!”

A movement in South Korea to recognize the health consequences of toxic exposure for semiconductor workers has slowly amassed political, social, and cultural gravity over the course of a decade. For much of that time, Samsung waged an often bitter and public battle with the families of dead or sick workers. The company paid some of the nation’s top lawyers to fight workers’ compensation claims—a remarkable step, given that payments were from a government insurance pool, not the company. Executives were secretly recorded offering or paying families money in exchange for withdrawing their claims and keeping quiet. By 2014, following growing international attention and the domestic release of Another Promise, a dramatic film about the fight, the tide had turned. The government stopped rejecting compensation claims outright, and courts backed workers in a handful of cases. Finally, Samsung apologized publicly for the way it treated the families.

Although both Samsung and SK Hynix continue to deny there’s any causal link, both companies began by early last year to privately compensate current and former workers or their families for illnesses and deaths. Samsung also brought in an outside committee to recommend health and safety changes, and its work continues, says Suh, the Samsung spokesman. He says the company’s overall stance on these issues has changed significantly in just a few years: “We have been working to help out former semiconductor employees and their families who have endured the hardship and heartache.”

Even so, Samsung and SK Hynix have been inconsistent in paying claims for reproductive-health effects, the most consistently documented dangers in the industry. They pay for cases of infertility or miscarriages only for women who are still with the company. (Current and former employees of both companies are eligible for payments if their children were born with birth defects or suffered childhood cancers and similar diseases.) SK Hynix said in 2016 that miscarriages made up the biggest share of all approved cases, or about 40 percent.

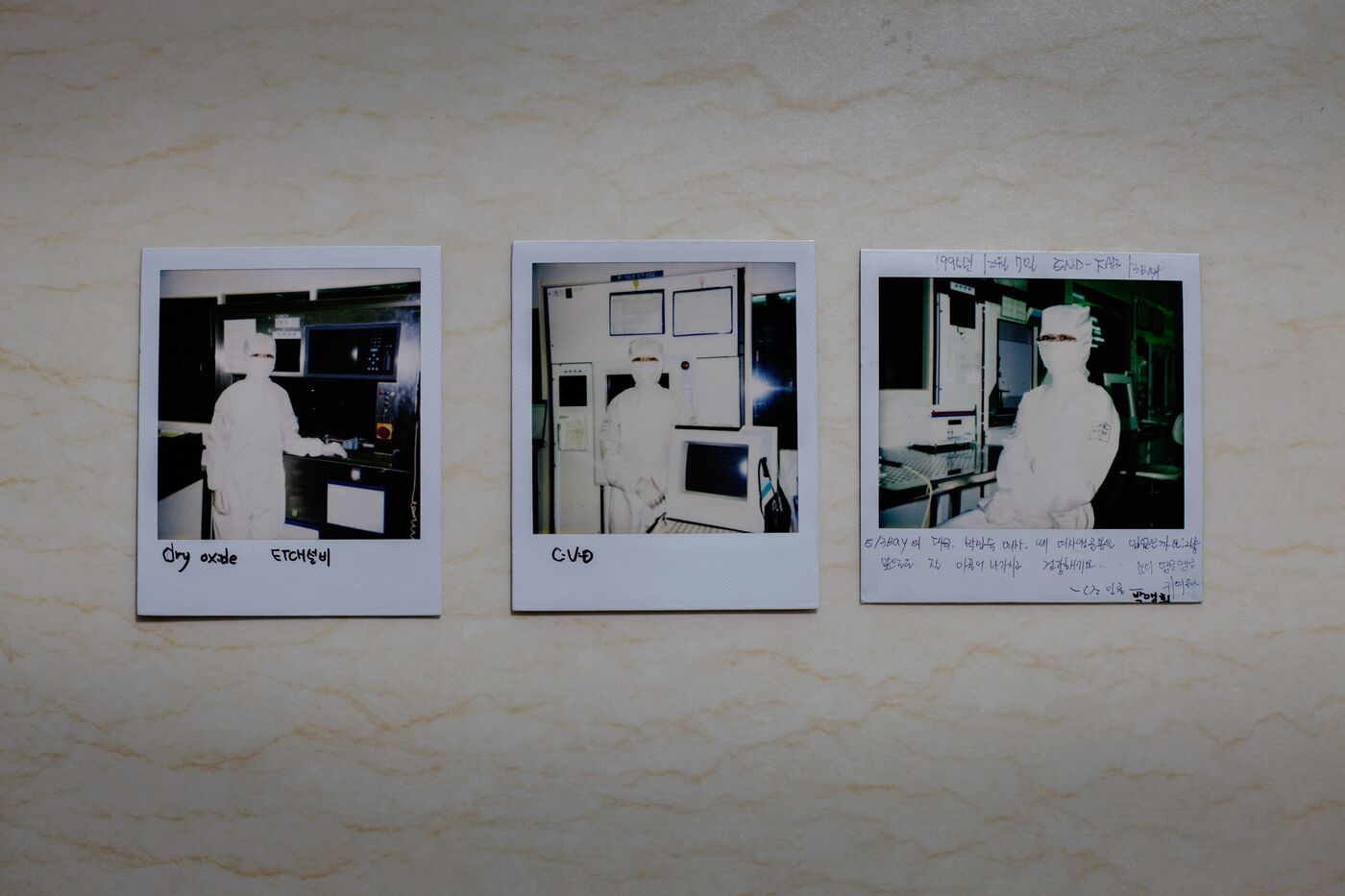

In a high-rise apartment south of Seoul, I meet Kim Mi-yeon, a 38-year-old who started working for Samsung in 1997, one week after graduating from high school. Her parents were farmers; the four-hour bus ride to Samsung’s global chipmaking headquarters in the city of Suwon marked the first time Kim had ever left home.

She was shocked at the operation’s scale, as buses ferried her and other young women around, including to the dormitories where they lived. “It felt more like a city than a company,” she says. She was a production worker in the packaging and testing department, so it’s unlikely her job put her in direct contact with photoresists and strippers. But she came in constant contact with other women who worked in cleanrooms. Within a couple of years, she noticed her periods changed.

In December 2007 she married a contractor she met at Samsung. They tried to have a family, but in August 2008, doctors told her she was almost infertile. Treatments failed, as did attempts at in vitro fertilization. In March 2012 doctors discovered a mass growing inside her uterus. She underwent surgery and multiple rounds of drug treatment, but, desperate for a child, she rejected recommendations that she have her uterus removed. She quit Samsung the next month, after 15 years. She then applied to the workers’ compensation board.

In March the government formally recognized her as the first semiconductor worker to suffer an occupational illness related to reproductive health. Her case took five years. “I’m very happy now,” she says, holding her 10-month-old daughter, conceived through artificial insemination.

Kim, the public-health researcher, says it’s impossible to estimate how many women might have been exposed to EGEs and reproductive-health dangers in South Korea and beyond. Turnover rates are high in microelectronics plants, and even the estimate of 120,000 women in South Korea’s industry doesn’t include a large number of temporary workers and subcontractors. The scientists at SK Hynix found that many production workers perform multiple tasks, adding to the challenge of figuring out who’s exposed to what. Women are also critical to the industry in Taiwan, Singapore, and Malaysia, which have all relied heavily on foreign migrant workers. And EGEs may not be the only culprits, or even the main ones, behind continuing reproductive-health effects, given the pervasiveness of toxic chemicals and the secrecy surrounding them.

After the Digital Equipment investigation 30 years ago, Pastides’s academic career advanced steadily and impressively. Today he’s the president of the University of South Carolina, a post he’s held since 2008. But the memories of the Super Bowl Sunday tribunal and the pressure he faced from the world’s top technology companies still make him feel somewhat anxious. And controversy lingered for years. “That was something unprecedented to me. I didn’t expect it,” he says. “And frankly I had difficulty coping with it at times.”

His work on the Digital Equipment study certainly remains untarnished. But he’s moved on to other concerns. And when I tell him the reforms in the microelectronics industry don’t appear to have been as deep or as wide as he believed, he seems shaken. “That is terrible news,” he says. He gathers himself, ever the scientist. “The fact that women around the world were still being subjected to things that experts, including corporate leaders, decided should not be used in the workplace—to me that is an extremely sad story, and a loss for public health.” —With Ben Elgin, Wenxin Fan, Heesu Lee, and Kanoko Matsuyama